A deep and genuine relationship with the Earth has long been a central tenet of First Nations worldviews and philosophy. Long before the mainstream construct of "Mother Earth" became popular, the First Nations, Inuit, and later Metis people truly connected with the Earth as their Mother. The natural world is considered home, and the rightful stance to take upon her is a respectful, interconnected one of stewardship and gratitude.

A deep and genuine relationship with the Earth has long been a central tenet of First Nations worldviews and philosophy. Long before the mainstream construct of "Mother Earth" became popular, the First Nations, Inuit, and later Metis people truly connected with the Earth as their Mother. The natural world is considered home, and the rightful stance to take upon her is a respectful, interconnected one of stewardship and gratitude.

This relationship went further than just a powerful connection - over the millennia, First Nations and Inuit people developed intricate knowledge and understanding of the natural world. Their awareness of global laws and patterns is equal to and even exceeds mainstream scientific knowledge and offers clues to our continued survival on this planet. Their keen understanding of weather, seasons, geography, animal behaviours and patterns, plant growth, sea and water fluctuations, soil protection, gardening, ethnobotany, ecology, astronomy, and other natural knowledge is sophisticated and has been validated repeatedly over generations.

For countless generations, the First Nations and Inuit people have had unique, respectful and sacred ties to the land that sustained them. They do not claim ownership of the Earth, but rather, declare a sense of stewardship towards the land and all of its creatures. This sense of responsibility towards the land is more than a mental or even emotional obligation; it is tied intrinsically to Spirit. A strong communion with the spirit of all aspects of the earth provides a unique perceptual lens through which all activities of daily life become an expression of Spirit.

First Nations, Inuit, and Metis knowledge is strongly linked to the natural world: Indigenous languages, cultural practices, and oral traditions are all intimately connected to the Earth. Traditionally, First Nations and Inuit people see their relationship with each other and with the Earth as an interconnected web of life, which manifests as a complex ecosystem of relationships. Balance and holistic harmony are essential tenets of this knowledge and subsequent cultural practices. Embedded too is a keen belief in both adaptability and change, but change that further promotes balance and harmony, not change that creates distress, death, and the depletion of the Earth’s populations and resources. Careful observation of the seasons and the cycles of life foster an appreciation for the impermanence of things, including humans, as well as the interdependence of all life forms with each other.

A relatively recent, evolving interest in First Nations knowledge by mainstream society is both timely and to be expected. The deep sophisticated knowledge of how to live in balance with other people and all of the Earth’s inhabitants, and the very planet, herself is keenly necessary in the 21st century. Many First Nations, Inuit and Métis Elders have mused that if Western peoples had paid attention to Indigenous knowledge when they first arrived in Canada and other parts of the Americas, the current world would be much more harmonious, clean, and healthy. Now that some people are willing to listen, after decades of land mismanagement, pollution, greed, and serious depletion of animal, plant and other sources of sustenance, some keepers of Indigenous knowledge are willing to share. “One of our truths is to share. We have chosen to share our stories, our teachings, our practices, our linguistic references and maps in order that the knowledge and the wisdom that has sustained us as Coastal peoples can be understood and used by others, as we have adapted to change so must mainstream society”: (Brown & Brown, 2009, p. 6).

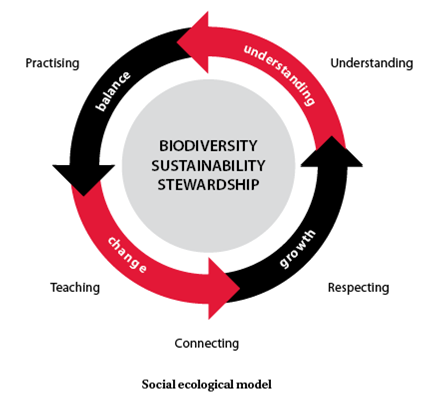

The following model was designed by Brown and Brown (2009, p. 10) to illustrate the circular process of understanding the world around us, sharing this understanding, and contributing to the knowledge and health of all by cultivating universal stewardship to promote biodiversity and sustainability.

READ: Brown, F. & Brown, K. (2009). Staying the course, staying alive. Coastal First Nations fundamental truths: Biodiversity, stewardship and sustainability. Victoria, BC: Biodiversity BC. http://www.biodiversitybc.org/assets/Default/BBC_Staying_the_Course_Web.pdf

READ: Haig-Brown, C., & Dannenmann, K. (2002). Pedagogy of the land: Dreams of respectful relations. McGill Journal of Education, Fall. http://mje.mcgill.ca/article/view/8649/6592.pdf

VISUAL MODEL: Create a visual model to illustrate the role of stewardship and interconnectedness in First Nations, Inuit, and Metis knowledge. Include ways that these roles can be integrated into education for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners.